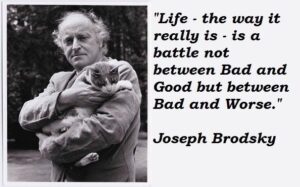

Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996), a Russian-American writer and writer, remains one of the most celebrated scholarly figures of the twentieth hundred years. His works, set apart by scholarly profundity, semantic dominance, and significant comprehension of human instinct, procured him the Nobel Prize in Writing in 1987. Brought into the world in Leningrad, Brodsky confronted mistreatment in the Soviet Association for his “parasitic” way of life as a writer, prompting his possible exile in 1972. Getting comfortable in the US, he turned into a US Writer Laureate and made a permanent imprint on worldwide writing.

Brodsky’s statements mirror his sharp perceptions of life, love, time, and artistry. They resound with all-inclusive insights, offering shrewdness that rises above social and transient limits. Whether tending to the intricacies of presence or the magnificence of language, his words motivate reflection and a more profound appreciation for our general surroundings. This assortment of statements observes Brodsky’s inheritance, exhibiting his capacity to distill significant thoughts into exquisite, intriguing articulations.

Early Life and Birth

Joseph Brodsky was brought into the world on May 24, 1940, in Leningrad (presently St. Petersburg), Russia. His original name was Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky. The violent scenery of Soviet Russia formed Brodsky’s initial life during the time. His dad, Aleksandr Brodsky, was a modern designer, while his mom, Maria Brodskaya, filled in as a financial expert. His initial years were set apart by the difficulties of The Second Great War, as Leningrad got through a severe attack by Nazi powers from 1941 to 1944. This experience profoundly impacted Brodsky’s perspective.

Brodsky’s family was Jewish, and this legacy would later shape his character, both as an essayist and regarding the Soviet enemy of Semitism. His childhood in Leningrad, during a time of philosophical concealment, control, and political strain, molded his scholarly interest and profound obligation to write.

Education and Early Intellectual Development

Joseph Brodsky’s proper training was brief. He went to class in Leningrad, but he was not a model understudy. His inclinations were toward writing, history, and artistic expression instead of formal scholarly subjects. He exited secondary school at 15 years old, which drove him to different unspecialized temp jobs. He remembers working for a meat-pressing plant and as a worker in a development group. During this period, Brodsky’s energy for verse escalated.

Despite his initial lack of formal schooling, Brodsky was an unquenchable reader, devouring works of Russian and European writing. He is self-taught by perusing the extraordinary works of Russian artists like Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva and Western essayists like William Shakespeare, W.B. Yeats, and T.S. Eliot. This free instruction established the groundwork for his future abstract vocation.

Early Career and First Poems

Brodsky’s excursion into verse started in his young years when he started composing sonnets, at first in Russian. As he developed, his sonnets were affected by the intricacy and thwarted expectations of Soviet life, as well as the impact of Western writing that must be perused covertly because of the Soviet system’s severe control regulations.

In his mid-20s, Brodsky gained recognition for his sonnets and started participating in the artistic underground of Leningrad. Nonetheless, his ascent to recognition was difficult. His questionable verse, which frequently addressed topics of existentialism, independence, and the grimness of life under Soviet rule, soon made him an objective of public authority.

Exile and Legal Trouble

In 1964, at 24 years old, Brodsky was captured by the Soviet experts on charges of “parasitism,” which basically implied that he was not working in a formally endorsed calling. This charge was generally an impression of Brodsky’s refusal to forsake his verse to adjust to the public authority’s assumptions.

Brodsky’s preliminary in 1964 drew the attention of various scholars and artisans. He was condemned to five years of arduous work; however, he spent much of his sentence in jail rather than in a work camp. The preliminary and the resulting exile symbolized the severe environment in the Soviet Association at that time, where dissenter scholars confronted mistreatment.

In 1972, in the wake of persevering through the brutal states of jail and constrained work, Brodsky was permitted to emigrate to the US. He had been banished from his country, and this constrained movement would profoundly influence his work and personality.

Life in the United States and Academic Success

After arriving in the U.S., Brodsky confronted enormous difficulties, including language barriers and monetary challenges. However, his incredible gifts as a writer immediately earned him recognition in scholarly circles. At first, he maintained modest sources of income; however, over the long haul, Brodsky found his spot in the abstract local area, giving talks and readings. His beautiful voice was strong, and his experience as an untouchable in the U.S. gave him an interesting viewpoint that enhanced his composition.

Brodsky’s scholarly profession took off after he was welcomed to instruct at different colleges, including the College of Michigan and Yale College. In 1977, I became an English teacher at the renowned Southampton School in New York. Afterward, he would stand firm on a footing at the College of Michigan. Brodsky’s showing vocation was a massive piece of his later life, as he imparted his immense scholarly information to understudies and coached more youthful writers.

Achievements and Success

Brodsky’s artistic progress in the US was fleeting. He became one of the most noticeable banished Russian authors in the Western world. His verses, articles, and interpretations caught the scholarly and profound intricacies of his exile and his encounters. In 1987, he was granted the Nobel Prize in Writing, an affirmation of his striking commitment to the abstract world.

Notwithstanding the Nobel Prize, Brodsky received various honors, including the Public Enrichment for HumaExpressionon Cooperation and the MacArthur Association. His works were converted into different dialects, solidifying his situation as one of the leading artists of the twentieth hundred years.

Brodsky’s Major Works

Brodsky’s collection of works is different, yet his verse stays at the core of his abstract heritage. His significant assortments include A Grammatical Form(1980), To Urania (1988,) and tc. (1996), which shows his remarkable, incredible voice, portrayed by profundity, scholarly thoroughness, and a feeling of exile.

His papers, short of What One (1986), consider topics ranging from writing and reasoning to the individual battles of being an émigré. Brodsky’s work frequently covered Eastern European and Western artistic practices, and his sonnets mirrored his commitment to history, governmental issues, and the human condition.

Personal Life and Relationships

The intricacy and steady strain set Brodsky’s life apart between his way of life as a writer and the viable fundamental factors of life in banishment. During the 1970s, he was hitched momentarily to his most memorable spouse, Maria Soledad, yet the marriage ended separately. Brodsky had a convoluted relationship with affection and frequently communicated subjects of isolation and segregation in his verse.

His companionships were crucial for his feeling of belonging, especially his associations with other savvy people and journalists. Brodsky was near the essayist and interpreter Robert Lowell, who likewise played a critical role in advancing his work in the U.S. Despite the difficulties of exile, Brodsky remained mentally drawn in and sought associations with other artistic figures.

Brodsky’s Habits and Writing Style

Brodsky was known for his restrained work habits. He frequently composed promptly at the beginning of the day when his mind was fresh. His creative cycle was not unconstrained; it was a work of scholarly thoroughness and imaginative thought. He took time with each line and verse, frequently reworking and amending his job to ensure it satisfied his demanding guidelines.

Brodsky was likewise an eager peruser, and his composing was profoundly educated by the works regarding different artists and thinkers. He had a specific interest in traditional writers, particularly those of the long past, which impacted his way of dealing with both structure and content. His verse was, much of the time, described by thick symbolism, scholarly intricacy, and a rich, formal design.

Brodsky’s Views on Exile and the Role of the Poet

Exile became a focal point in Brodsky’s life and work. Although he had been driven away from the Soviet Association, he came to see exile as a developmental encounter that shaped his way of life as a writer. In his exposition, Short of What One, Brodsky ponders the idea of exile, suggesting that it can act as a wellspring of imagination and self-revelation.

For Brodsky, the writer’s job was to mirror the reality of the human experience, defy the intricacies of the world, and express them eloquently in language. He accepted that verse could rise above borders and interface individuals across existence, which was particularly significant given his experience of being banished from his country.

Favorite Things and Interests

Brodsky had a pold-style over w, which was old-style music exceptionally crafted by Bach, and he frequently referred to music in his verse. He additionally appreciated writing from different practices, including Russian, English, and Italian. Moreover, Brodsky had an extraordinary affection for European urban communities like Venice, which he frequently visited and expounded on. Venice, with its rich history and piercing excellence, turned into a significant illustration in his work for topics of rot, exile, and the progression of time.

Brodsky additionally valued fine food, wine, and scholarly discussion. He appreciated investing energy in bistros and scholarly social occasions, where he could talk about thoughts and writing with individual authors and artisans.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Joseph Brodsky?

Joseph Brodsky was a Russian-American writer, writer, and interpreter, generally viewed as one of the leading scholarly figures of the twentieth 100 years. He won the Nobel Prize in Writing in 1991 for his “comprehensive creation,” enveloping verse, expositions, and interpretations.

What is a remarkable Joseph Brodsky quote finally?

Perhaps one of his most well-known expressions on time is:

“Time is an incredible instructor, yet sadly, it kills every one of its students.”

What did Joseph Brodsky say regarding isolation?

Brodsky frequently talked about the significance of isolation. He once said:

“I believe that the more you can acknowledge isolation, the more you can partake in the organization of others.”

Did Brodsky have any reflections on composition?

Brodsky accepted that composing was a course of individual change. He expressed:

“The central thing is to keep the most compelling thing the primary thing.”

What is Joseph Brodsky’s view on satisfaction?

Brodsky was known for his philosophical thoughts on bliss. He commented:

“Joy is the most elevated great, and the most elevated great is never served by culminating something, yet by parting with it.”

How did Brodsky portray the job of the artist in the public eye?

He saw the artist’s job as one of obligation and moral clearness. He said:

“A writer’s work… is to be a guide or the like, not to be a reflection of society.”

What did Brodsky understand regarding the human condition?

Brodsky’s appearance on human instinct frequently had a melancholic edge. One such statement is:

“A person is an animal that must be continually helped to remember the way that he is mortal.”

What did Joseph Brodsky say regarding the importance of life?

Brodsky’s contemplations on life were many times profound and complex. He once said:

“The significance of life is the most pressing, everything being equal.”

Conclusion

Joseph Brodsky’s statements mirror a profound commitment to life’s intricacies, mixing scholarly meticulousness with idyllic understanding. His appearance on time, isolation, satisfaction, and the job of the writer underlines the human condition’s subtleties — its mortality, temporariness, and potential for change. Brodsky’s words challenge perusers to think about the more profound implications of presence and the obligations of the author to society. Whether examining time’s section or the quest for satisfaction, Brodsky’s work perseveres through the use of language to investigate, question, and finally figure out the secrets of life.